Wisconsin’s most historic and bloody labor incident occurred on May 5, 1886 on the shores of Lake Michigan in the Bay View area of Milwaukee. That day dawned after four days of massive worker demonstrations throughout Milwaukee on behalf of the creation of eight-hour day laws..

As some 1,500 workers marched toward the Bay View Rolling Mills (then the area’s biggest manufacturer) urging the workers thereto join the marches, the State Militia lined up on a hill, guns poised. The marchers were ordered to stop form some 200 yards away; when they didn’t, the militiamen fired into the crowd, killing seven persons.

The marchers dispersed and the eight-hour days marches ended. The incident, in spite of its immediate end to eight-hour day efforts, spurred workers and their families to look forward to build a more progressive society in Milwaukee and Wisconsin.

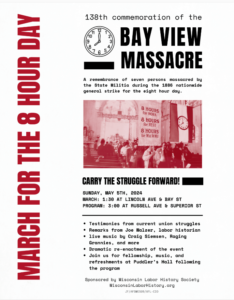

Each year, more than 200 persons gather, under the sponsorship of the Wisconsin Labor History Society, at the Bay View Rolling Mills historical marker site at S. Superior St. and E. Russell Ave. in Milwaukee to commemorate this incident.

This year’s event was held Sunday, May 5, 2024 at the site, featuring the re-enactment of the 1886 massacre, songs by Craig Siemsen, prominent local folksinger, and the Raging Grannies. Remarks were made by Joe Walzer, professor of history at UW-Milwaukee.

- A march that followed the route of the 1886 8-hour day marchers, starting at E. Lincoln Ave and S. Bay St..was held before the event. An

- after-event reception was held at historic Puddlers Hall, 2461 S St Clair St.

For a full report on the 2024 event, see the summer edition of the WLHS newsletter.

historians discuss significance of

In 2020, WLHS sponsored a virtual forum with four historians discussing the significance of the event. This 25-minute video, entitled “The Bay View Tragedy: Remembering Champions in the Fight for the 8-Hour Day,” was premiered on May 1 (May Day 2020) in an online program. View it here.

Study Guide: The Bay View Tragedy and Its Impact

A Study Guide full of background information and questions that will lead to interesting discussions. Click here.

View two video supplements to study guide:

Overview of MAY 2012 event.

Remarks of John Gurda at May 2012 event.

______________________________

Other Resources, Reports of Past Commemorations

Remarks of Stephanie Bloomingdale at 2012 event

For a bibliography, click here.

The front page of Wisconsin State Journal, May 6, 1886.

Readable version of the Bay View Tragedy report from Wisconsin State Journal, May 6, 1886.

The Trials of Paul Grottkau, a leader of 1886 event.

_______________________

Suggested Readings

Workers and Unions in Wisconsin History: A Labor History Anthology. By Darryl Holter. State Historical Society of Wisconsin. 1999. (See Pages 34-46 “The Bay View Tragedy,” by Robert Nesbit, an excerpt from The History of Wisconsin, Volume III, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison, 1985.)

Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee. By Thomas W. Gavett. University of Wisconsin Press. Madison, Wis., 1965. (See Pages 50-71: Chapter 5 – RIOT!) NOTE: This book is out of print, but may be available in major Wisconsin libraries. The Labor Movement in Wisconsin: A History. By Robert W. Ozanne, State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Madison, Wis. 1984. (Chapter One: “The First Unions”)

Additional Readings Labor’s Untold Story. By Richard O. Boyer and Herbert M. Morais. United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE), 1965 (Second Edition). (See Pages 65-104: Chapter III – The Iron Heel).

The Badger State: A Documentary History of Wisconsin. By Barbara and Justus Paul. October 1979. (See Pages 341-351.

May Day: A Short History of the International Workers’ Holiday 1886-1986. By Philip S. Foner. International Publishers. New York. 1986.

The American: A Middle Western Legend. By Howard Fast. Duell, Sloan & Pearce. 1946. This novel was a best seller when published more than 50 years ago. It tells the story of John Peter Altgeld, an Illinois governor who showed surprising political courage in the aftermath of the Haymarket Tragedy.

Big Trouble: A Murder in a Small Western Town Sets Off a Struggle for the Soul of America. By J. Anthony Lukas. Simon % Schuster. 1997. Although this concerns an 1890s labor struggle in the Idaho mines, the author traces much labor history in the late 19th Century, including mentions of Wisconsin incidents. A large book, but worth it for interested readers. For an extensive Labor History reference list please visit the Wisconsin Labor History Society Reference Page.

Suggested web sites

A good start into the web is through the Wisconsin State AFL-CIO site, www.wisaflcio.org. Click on “labor history” and find other links, plus a good bibliography. And, there’s our sister society, the Illinois Labor History website at www.kentlaw.edu/ilhs/.

Reports from previous Commemorations:

Report from 129th Anniversary Commemoration – Jenifer Epps-Addison, speaker

Report from 131st Anniversary Commemoration – Luz Sosa, speaker

View video of the 2012 celebration

Read Excerpts: Remarks of Amy Stear at Bay View Tragedy event, May 3, 2009 (Amy Stear, Wisconsin director of 9to5, spoke at 123rd Anniversary Commemoration of the Bay View Tragedy, May 3, 2009, in Milwaukee. Read the remarks here.)

Read Report of Rep. Gwen Moore’s remarks to 122nd Anniversary Commemoration on May 4, 2008.

For report on event in May, 2007, click at may 07 BV.pdf and for the May 2006 event, click at may 06 BV.pdf .

A BRIEF HISTORY:

From the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Sunday, April 30, 1995

When Bay View strike turned to bloodshed

Troops opened fire on workers demanding eight-hour day

by John Gurda

We gather each year to remember a tragedy. The date, May 5, is always the same, and the place is always the site of a vanished steel mill in Bay View. Even the people are generally the same, a motley bunch that includes union activists, college professors, Bay View residents, and former mayor Frank Zeidler, the group’s godfather.

The tragedy we remember took place in the first week of May, 1886. For a few days in that long-ago spring, Milwaukee was practically unhinged. A general strike, affecting everyone from bakers to brewers, began on May 1 and soon brought the city to a grinding halt. On May 2, nearly 15,000 striking workers massed for the largest parade in Milwaukee’s history to that time. By May 4, after a series of less orderly demonstrations, Gov. Jeremiah Rusk had called out the militia.

One day later, horrified spectators witnessed the bloodiest labor disturbance in Wisconsin’s history.

What issue could have aroused such passions? Nothing more or less than the eight-hour day. Milwaukee was a stronghold of the Eight-Hour League agitation that swept the nation in 1886. Here and elsewhere, most workers routinely put in 10 to 12 hours a day, six days a week, for only a dollar or two a day. As the industrial work force grew from a disorganized mass to a well-defined movement, the eight-hour day, without a cut in pay, became its “password and battle cry.” A celebrated slogan summed up the movement’s core demand: “Eight Hours for Work, Eight Hours for Rest, Eight Hours for What We Will.”

The springtime campaign produced a number of victories. Milwaukee’s Common Council passed an eight-hour ordinance for municipal workers before labor’s May 1 deadline, and more than 20 private employers followed suit.

The general strike of early May was a direct response to companies that refused to adopt the new system. Using both persuasion and intimidation, the strikers soon shut down every major employer in the city, with a lone exception: the North Chicago Rolling Mills, a massive steel plant in suburban Bay View. On May 4, a group of laborers, many of them Polish immigrants, resolved to bring the mill’s leaders to heel. Nearly 700 of them gathered at St. Stanislaus Church, on the corner of 5th and Mitchell Sts., for a brisk morning walk to Bay View. When a conference with mill executives there proved fruitless, the laborers served notice that they would return.

“Uncle Jerry” Rusk called out the militia in the meantime, and the troops spent an uneasy night inside the plant gates. On the morning of May 5, they faced a phalanx of marching workers that had swelled to at least 1,500. As the crowd surged down Bay St.toward the mill, the militia commander ordered them to disperse. At a distance of 200 yards, it is doubtful that the marchers heard him above their own noise.

When they continued to advance, the commander ordered his troops to open fire. At least seven people fell dead or dying, including a 12-year-old schoolboy and a retired mill worker who was watching the commotion from his backyard. The rest of the crowd beat a hasty retreat to the city.

Reactions to the incident varied wildly. Most Milwaukeeans were appalled by the carnage, but many considered the militia’s actions justified. “I seen my duty and 1 done it,” crowed Gov. Rusk, staking his position as a champion of law and order. Others took the shootings as chilling evidence that industrial property was valued more highly than industrial workers.

The Bay View incident ended, for the time being, all efforts to institute the eight-hour day, but it also galvanized Milwaukee’s workers. In the fall elections of 1886, the labor-oriented People’s Party elected a congressman, several state legislators and an entire slate of county officials. Although their triumph was only temporary, it was the first tremor in a political upheaval that carried a socialist, Emil Seidel, into the mayor’s office in 1910. John Gurda is a Milwaukee writer and historian.